by RACHAEL HANLY & LUANA SAWMYNADEN

This week’s rec: Leonardo Da Vinci’s (1452-1519) anatomical drawings

Medium: Pen and ink

“A good painter has two chief objects to paint — man and the intention of his soul. The former is easy, the latter hard, for it must be expressed by gestures and the movement of the limbs.”

– Leonardo Da Vinci

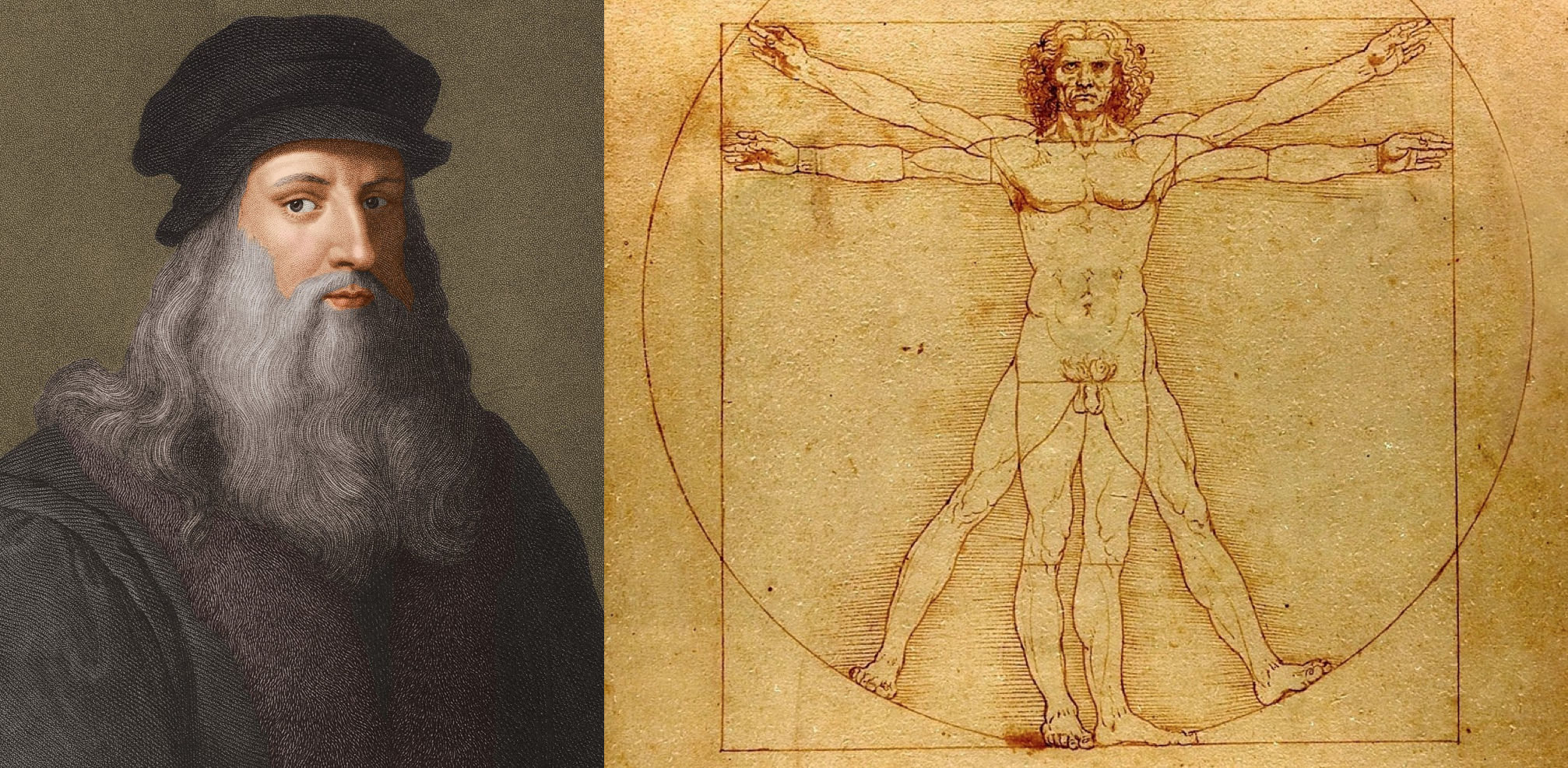

Leonardo da Vinci was the archetypal Renaissance man. With interests spanning invention, engineering, cartography, mathematics, history, architecture, music, painting and beyond, we rarely give him the credit he deserves as a revolutionary whose obsessive dedication to the study of the human body showcases a scientific mind far ahead of its time. Despite being possibly the most celebrated artist in history, perhaps even more interesting than the mystery of the Mona Lisa is the shocking accuracy with which Da Vinci was able to understand human anatomy and its relevance to modern medicine.

Born in Florence in 1452, da Vinci was brought into a world at the centre of Renaissance Humanist thought. During his apprenticeship under Andrea del Verroccio he had been encouraged to gain an appreciation of the study of anatomy, and his strength in this area allowed him access to hospitals in Florence, Milan and Rome, where he was permitted to dissect human corpses for further study.

Da Vinci strongly believed in the power of sight, which was, in his opinion, humanity’s most trusted and essential sense. He never ceased to highlight the importance of saper verdere; Knowing how to see. Striving to best capture the subject before him, Da Vinci’s anatomical drawings made use of the chiaroscuro technique, a style he largely pioneered in which strong contrasts between light and shadow are used to create a realistic three-dimensional effect. His studies in accuracy not only enabled him to depict more vividly human gestures and expressions, but he also witnessed the different mechanisms involved in bodily movements and conveying emotions.

During Da Vinci’s time, little was known about human anatomy, with most discoveries largely based on animal dissections. Leonardo, being a reputable Florentine figure and having sufficient influence to lead post-mortem examinations, was one of the first to gain access to fresh human cadavers, mainly of recently executed criminals. His drawings of a foetus in utero, sex organs and other bony and muscular structures were also some of the first in history. The work was tedious, with no proper methods for embalming bodies, which led to their quick decomposition within 3 days. However, his commitment and curiosity were formidable opponents to the biological time-limit placed on his studies.

During Da Vinci’s time, little was known about human anatomy, with most discoveries largely based on animal dissections. Leonardo, being a reputable Florentine figure and having sufficient influence to lead post-mortem examinations, was one of the first to gain access to fresh human cadavers, mainly of recently executed criminals. His drawings of a foetus in utero, sex organs and other bony and muscular structures were also some of the first in history. The work was tedious, with no proper methods for embalming bodies, which led to their quick decomposition within 3 days. However, his commitment and curiosity were formidable opponents to the biological time-limit placed on his studies.

His more detailed anatomical studies began in 1506, when he made the acquaintance of el vechio – the old man – in a hospital in Florence, who claimed to have been more than 100 years old. “And thus, without any movement or sign of any mishap, he passed from this life. And I dissected him to see the cause of so sweet a death”, wrote Leonardo, who by the time had already conducted 10 human dissections. His notes from the centenarian’s case documented the earliest known description of hepatic cirrhosis.

His more detailed anatomical studies began in 1506, when he made the acquaintance of el vechio – the old man – in a hospital in Florence, who claimed to have been more than 100 years old. “And thus, without any movement or sign of any mishap, he passed from this life. And I dissected him to see the cause of so sweet a death”, wrote Leonardo, who by the time had already conducted 10 human dissections. His notes from the centenarian’s case documented the earliest known description of hepatic cirrhosis.

In 1511, he dedicated his attention to the structure of the heart. His observations dismissed common misconceptions: his accurate descriptions of the 4 cardiac chambers rejected the two-chambered model of the time and he was first to affirm that the heart was at the core of the vascular system, otherwise attributed to the liver. He surpassed his peers by managing to describe cardiac movements, such as the contraction and relaxation of the atria and ventricles. While assisting a pig’s slaughter, he noticed the rotation of the spears inserted in its heart, which led to the discovery of cardiac twist, which happens when the heart empties itself, a mechanism which is currently subject of much discussion in regards to heart failure, where this ability is lost.

Indubitably, his most ingenious contribution was in 1513, with his recreation in glass of an ox’s heart while attempting to understand how the aortic valves ensured blood flow was unidirectional. He pumped a mixture of grass seeds suspended in water through his creation and witnessed little circular vortices, which assist in the closing of the valves, in the swelling of the root of the aorta – known 200 years later as the sinus of Valsalva. However, since his research was never made public, this phenomenon was never observed again until 1968, when two engineers from Oxford published an article in Nature heavily based on his work.

By the end of his life, in 1519, Da Vinci had conducted more than 30 human dissections and the 6,500 sheets from his notebooks were dispersed, undiscovered and unappreciated, until the 19th century. Unfortunately, this implied that Leonardo’s breathtaking discoveries did not have much historical impact on medical science, a tragedy, considering his life’s work contains some of history’s finest anatomical illustrations, with precision comparable to CT and MRI scans.

While sadly the fruits of da Vinci’s labour, lost to time, were unable to contribute largely to medical innovation, our knowledge in the present allows us insight into the mind of a brilliant scientist. It is in observing individuals like da Vinci that we can see how art and medicine intersect and at times rely on one another.