Written by Grace Smith, edited by Katerina Theocharous

Conspiracy theories have been around for ages. Dating back to medieval witch trials, the moon landing, Paul McCartney’s death… for some reason, we’ve always been fascinated by them. They can be exciting! They can also be dangerous. And both of these factors can be equally appealing. They’ve been around for ages, but they are particularly rife today, after a difficult 2 years of living in a global pandemic. And they can be about anything and everything, but they particularly plague the medical field – as I’m sure we now all know, after the past 2 years were made even more difficult by conspiracies about mask-wearing, vaccination, data-farming, and whether the pandemic was even real in the first place.

In our professional lives, we will inevitably have to confront these kinds of conspiracy theories, presented by patients, families, researchers, and policymakers alike. And this will inevitably present a great challenge as we deal with all those key stakeholders. If we can understand a little about the psychology of their making and appeal, then we can hopefully have more empathy and tact when faced with them in our careers.

I know that I, along with others, tend to assume that conspiracy theorists simply lack information, and that education and facts would ‘sort them out’. However, in reality theorists have plenty of facts – sure, they may consume some ‘alternative news’, but as a general rule they’re also still being exposed to all the same mainstream media as everyone else. The issue is more down to their creative interpretation of the facts. It’s about making the facts more exciting.

Conspiracy theorists want to feel privy to rare knowledge. In this context, it makes sense that obscure sources are deemed the most desirable and ‘reliable’. The ‘lone wolf’ seems more credible, despite the fact that it is heavily disputed, because they are controversial and have to fight for what they believe in. The rationale is that minority thinkers are actually on to something, and have separated themselves from the wolf pack with their higher thinking.

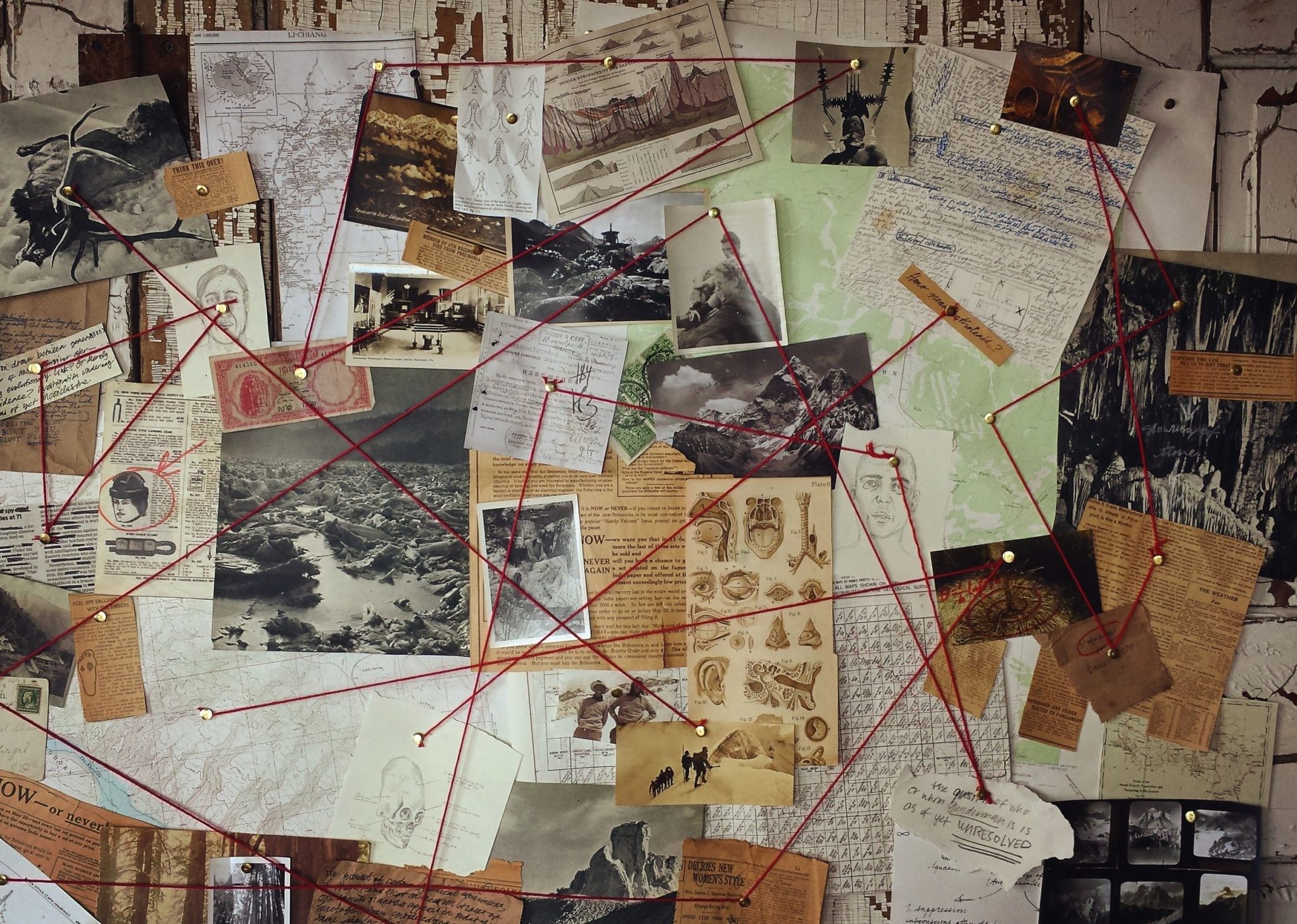

The pleasure of solving a puzzle, having details fall into place, that ‘lightbulb moment’ or ‘click’, is familiar to us all. It’s reflected in our strange fascination with crime shows and detective work – all of the clues are there on the screen waiting to be solved in the end. Theorists take the clues they have, and set about to construct a narrative with these scraps in order to solve a mystery and uncover a ‘hidden truth’.It’s a paradox: theorists see themselves as having their eyes wide open, when in reality their vision is clouded by their conviction that things can’t be as simple as they look .

The other important point is that conspiracy theories can be a form of escapism. Most conspiracy theories blame events on seemingly ‘preventable’ issues like corruption, inequality, and injustice, and these really do exist in the world. But simultaneously, there really is suffering out there that is unforeseen, unavoidable, and horrific. Rather than facing these two sets of facts head-on, it could be easier to take shortcuts in thinking and conflate them, delegating blame for awful events onto certain people because that creates hope that stopping the person can stop the event. It also may allow people to ‘make sense’ of harsh realities that are otherwise impossibly terrifying and confronting, such as 9/11 or, of course, a global pandemic Rather than acknowledging the horror of a new serious disease, shifting blame and using theories as an outlet for anger can provide an escape from the truth. But it also allowed confusion, frustration and fear to flourish during the pandemic, divided communities, and was a huge challenge for healthcare workers and vulnerable people.

However, the fact remains that if we were to banish all conspiracies, then the world would be a much more boring place. The reality is much less interesting than theorists like to believe, and what captures us most about historical conspiracies is often the aspect of ‘what if’.

So next time you hear a particularly lucrative version of the truth – a juicy conspiracy – think. Is this a plausible account of events? Possibly is it the easiest to believe in desperate times? Or is it simply the most fun?