written by RACHAEL HANLY

You may have recognised this type of print on t-shirts or posters – bold lines, bright colours and repeated use of symbols make for eye-catching motifs and are the signature of late American artist Keith Haring, activist and pop art icon of the 1980s who brought awareness to the AIDS crisis and emphasised the importance of accessibility in art. While his story chronicles the tragedy of a disease that plagued the gay community for an entire generation, it is also the colourful celebration of a life lived to the fullest, creating a legacy of hope, pride and brightness even in the darkest of times.

Haring began as a graffiti artist who created chalk drawings on empty spaces in subway stations, tagging his art with a shining, crawling baby known as “The Radiant Baby,” one of his most well-known symbols to date and inclusive of the religious symbolism he often employed in his works. His art is influenced by everything from experimental drugs to Dr Seuss and Looney Tunes cartoons, not to mention his own contemporaries, pop artists of the late 20th century who shifted the direction of art from traditional ideas of history and ethics to the celebration of culture and the everyday. “Because they were so fragile, people left them alone and respected them,” he said of his chalk drawings. The police did not know what to do with him; what he was doing was vandalism, but it could easily be erased. Furthermore, people were enthralled with his drawings and would gather to watch him work. Throughout the 80s, he befriended numerous contemporaries and famous figures including Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Roy Lichtenstein, Madonna and Yoko Ono. New York at the time was bursting with creativity, exploration and experimentation, and groups of artists gathered to share ideas, throw parties and hold exhibitions, with Haring organising events at Club 57, a spot frequented by the likes of Cyndi Lauper, Futura 2000 and RuPaul.

In 1986, Haring opened the Pop Shop, which allowed purchase of his art at accessible prices; however, the movement from underground art to commercialisation was widely criticised. He saw his art becoming more valuable in the art market, and the Pop Shop was a way in which he could remove his art as a commodity and present it as something that everyone could own a piece of. Critics, however, dismissed his art as aesthetically pleasing, relevant to time and place but with no significant universal value. Haring focused on the opinions of his contemporaries as well as the response from normal people not part of the art world, who he said responded “with complete honesty from deep down inside their hearts or their souls.”

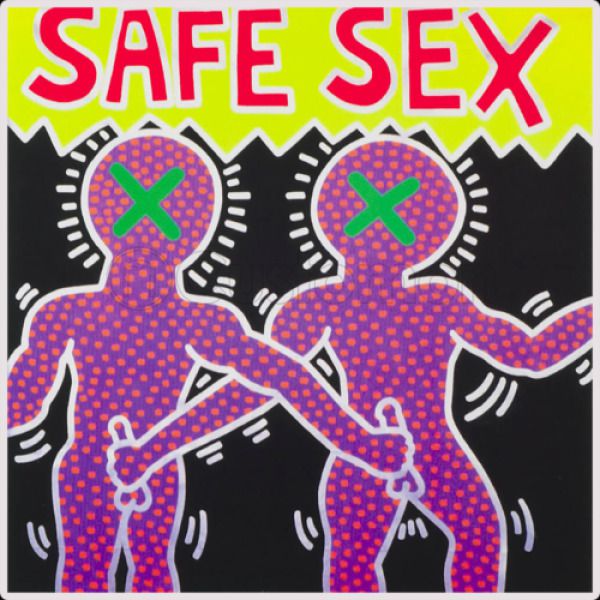

Haring had allowed his artwork to become a feature of popular culture without the inclusion of the art world, which he deemed ‘elitist,’ making his art affordable to the wider population and widening his scope for activism and political commentary. His art featured anti-Apartheid, anti-crack cocaine and AIDS and safe sex awareness messages, and his artwork was featured famously in performances by musical icons (including Madonna and Grace Jones) and even on the Berlin Wall. As a gay man, Haring’s art serves as a reflection of both the joys and struggles of his experience during the 80s; dynamic, simple and colourful line drawings juxtaposed with explicit imagery and messages illustrate the increasing freedom of sexual identity while also bringing into focus the fear and ignorance surrounding AIDS and its devastating impact as it swept through communities. Many had contracted HIV before they had known it existed – this sense of futility made it a scary time. Silence from governments and public backlash towards the LGBTQ+ community resulted in Haring having to watch many of his close friends die without treatment, and sadly he himself was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, but continued to work and advocate for HIV awareness until his death in 1990 at the age of 31.

Haring was an artist who portrayed multiple contrasting messages and feelings through his art; joy and sorrow, hope and awareness, intensity and simplicity. The accessibility of his art, though widely vilified at the time, serves as a reminder to approach life light-heartedly and disregard creative boundaries. But his story also reminds us of the dangers of ignorance and the importance of not turning away from uncomfortable truths. Though the AIDS crisis was a complex issue consisting of numerous factors that are difficult to convey, ultimately it is the role of medical practitioners to ensure that this sort of attitude towards disease is never perpetuated. In any case, Haring’s art lives on, not only as political commentary but as a playful celebration of the dynamic nature of existence and the pleasure of life.