by RACHAEL HANLY & LUANA SAWMYNADEN

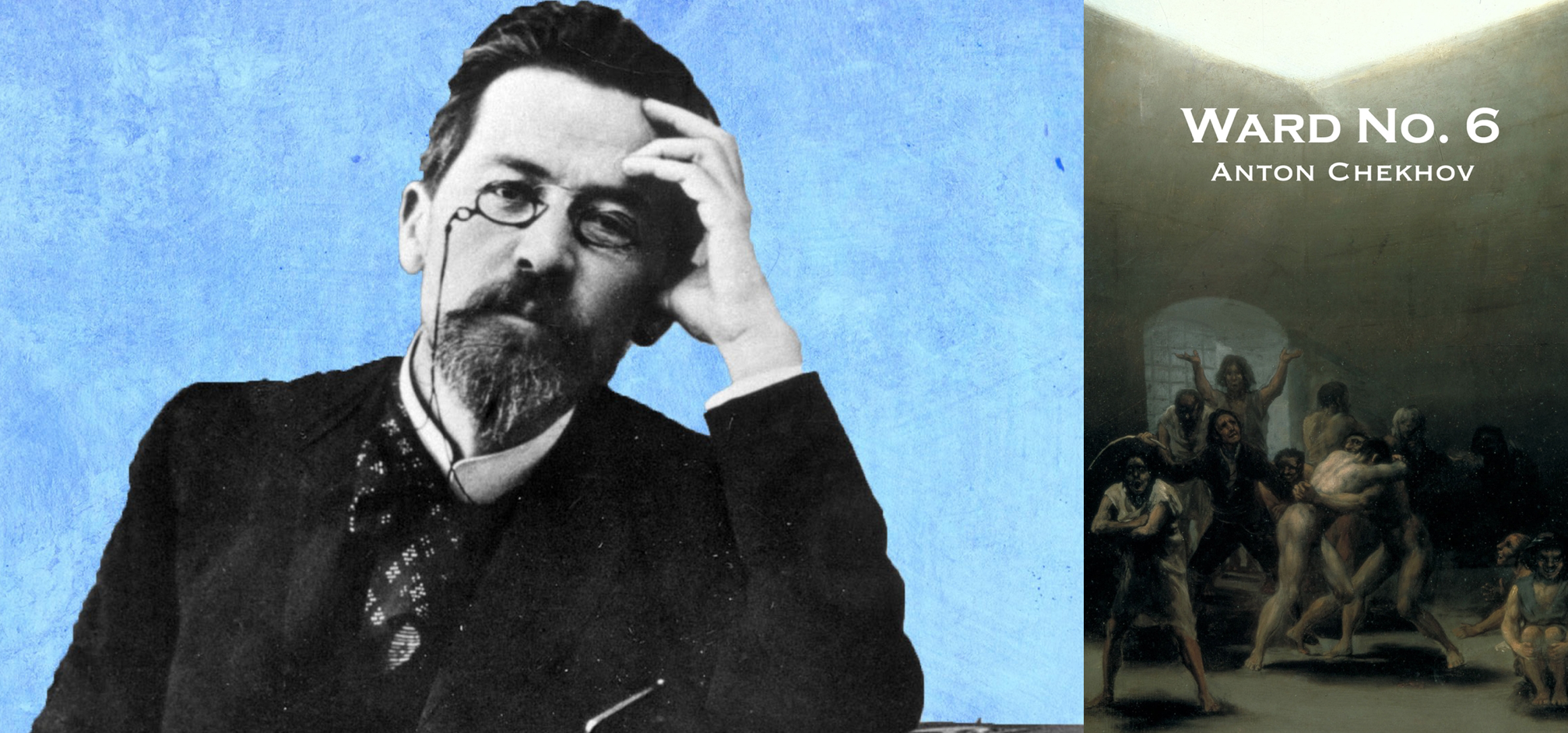

This week’s rec: Ward No. 6 (1892) by Anton Chekhov

Medium: Short fiction

![]()

“The ordinary man looks for good and evil in external things — that is, in carriages, in studies — but a thinking man looks for it in himself.”

Anton Chekhov was a Russian playwright/doctor born in the mid-19th century, most renowned for classics such as The Cherry Orchard (1904) and Three Sisters (1901), which cemented his legacy as a pioneer of modern theatre. Today we look at Ward Number 6, a short story living somewhat in the shadow of Chekhov’s most notable plays, but nonetheless a piece of literature that inspires challenging thoughts about mortality, the dangers of apathy and the importance of empathy as a medical practitioner.

Russian literature is oftentimes depressing. Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment comes to mind often- Chekhov’s bleak, open style of writing conjures images with startling ease and a stark, unforgiving sort of realism. We open with the hospital yard and an already established sense of hopelessness; “These nails, with their points upwards, and the fence, and the lodge itself, have that peculiar, desolate, God-forsaken look which is only found in our hospital and prison buildings.” Chekhov takes an interesting approach to descriptive writing: whereas most would linger on the beautiful, he chooses to display less glamorous aspects of everyday life. The scene is decrepit and unwelcoming; “chimney […] tumbling down”, “steps […] rotting away” and “mouldering”. His attention to detail is almost surgical: he meticulously dissects every scene, gets to the core of his characters by lifting off all of the layers one by one. One could also associate his literary approach to that of Zola and the other naturalists, but what differentiates him from the rest is his intriguing habit of finding beauty in the most unusual circumstances; “His grimaces are strange and abnormal, but the delicate lines traced on his face by profound, genuine suffering show intelligence and sense”. Chekhov has a surprisingly sardonic narrative voice (which again calls to mind his Russian predecessors) that gives readers reprieve from the dismal mood of which he writes.

Chekhov then goes on to describe the inhabitants of Ward Number 6, the psychiatric ward of the hospital in a remote, forgotten Russian town. We can barely call it a psychiatric ward, however, as we observe the filthy conditions of the hospital and abuse and isolation faced by its five occupants. It is believed the inspiration behind the asylum came from a horrifying visit to the Sakhalin prison. The doctor is Dr Andrey Yemifitch Ragin, whom Chekhov describes as a man who is “absolutely unable to give orders, to forbid things, and to insist.” Ragin, once a man who pursued his duties with fervent enthusiasm, has since become disillusioned with the state of healthcare in the town and has resigned himself to a life of depressing monotony. A series of coincidences lead to an encounter with Ward Number 6, where he finds company with the surly, intelligent Ivan Dmitritch. Here comes a set of intense philosophical conversations – Ragin, who lives in comparative luxury, believes that one can live apathetic of pain – Dmitritch, who has suffered all his life, believes it to be inescapable.

“A doctrine which advocates indifference to wealth and to the comforts of life, and a contempt for suffering and death, is quite unintelligible to the vast majority of men, since that majority has never known wealth or the comforts of life; and to despise suffering would mean to it despising life itself, since the whole existence of man is made up of the sensations of hunger, cold, injury, and a Hamlet-like dread of death.” This is not a surprising topic for Chekhov to choose – he himself suffered from tuberculosis for much of his short life, and often discussed mortality in his writings.

Chekhov has an almost childish way of writing- whether this is a feature of the English translation or whether it is intentional we do not know, but it makes for a devastating ending to the story – the absolute hopelessness of the situation is brought to its climax, and we witness a situation that is part absurd, part tragic; where we once felt frustration for Ragin, we now only feel pity.

The entire story is a goldmine for medically inclined minds. From the evolution of prescription drugs and natural alternatives (“castor oil”, “volatile ointment”) to the rather dreadful methods used by past medical professionals in an attempt to treat their patients’ mental health (e.g. pouring cold water on their heads), we can all be thankful for the much needed changes that ensued during the 20th century. Those with a particular affection for psychiatry will also enormously appreciate the fascinating but very bleak portrayal of the many mentally disturbed characters and the triggers that led to their descent to insanity.

Chekhov offers up a cautionary tale- we can’t fall victim to the comforts of our own lifestyle. But underlying this is a subtle disdain for authority that urges us to question established values, as well as an advocacy for those without a voice, particularly the mentally ill and those left behind by society. We must appreciate how far medical practice has come while still keeping a critical mind – it is the only way we can move forward.