by LUANA SAWMYNADEN (edited by RACHAEL HANLY)

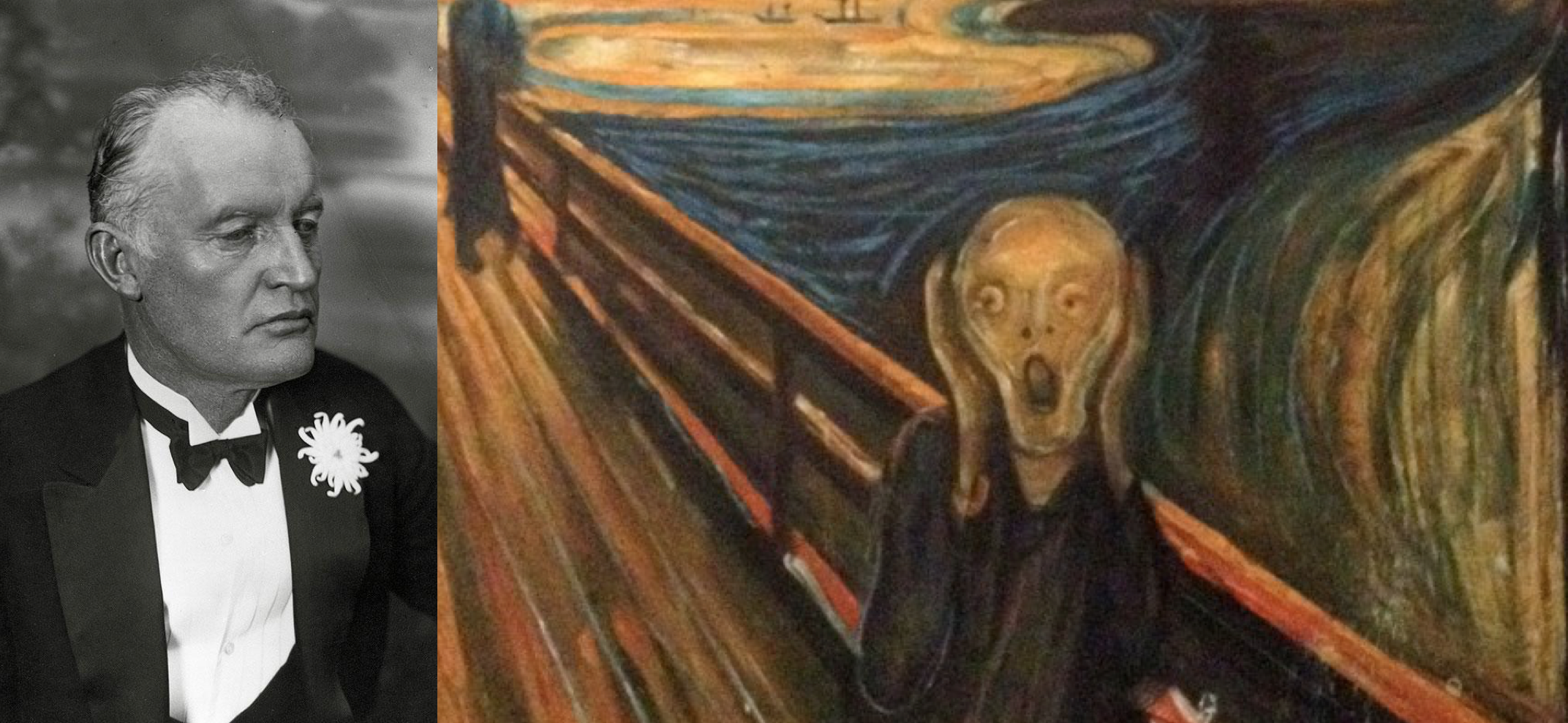

This week’s rec: The works of Edvard Munch (1863-1944)

Medium: Painting and printmaking

“I do not believe in the art which is not the compulsive result of man’s urge to open his heart.”

– Edvard Munch

One’s psychological state affects how they portray and express themselves, and painting is one art form that has always been a loyal outlet for articulating these ideas and feelings. While a diary provides a glimpse into one’s soul, brush strokes convey vivid descriptions of emotions when words fail to do them justice. Edvard Munch (1863-1944), a Norwegian expressionist painter and printmaker, led a tortured life, filled with afflictions, which deeply affected his sanity and inspired some of the most recognisable and influential artworks in modern history. However, Munch’s lifelong search to discover and fully understand himself led to the establishment of his “soul’s diary”; not only was he influenced by his own sufferings, he also unwaveringly recorded them in writing.

Munch’s style pertained to the Symbolist movement, since his real interest resided in the internal aspect of everything. His paintings aimed to reflect raw emotions and his inner subjectivity, as opposed to passively observing the exterior side of life. His art explored themes of repression and instability representative of his own mental anguish; they were deeper messages awaiting diagnostic interpretations. Death, love, sexual tension, terror, anxiety, loneliness and depression were all addressed through his use of contrasting lines, sombre tones, exaggerated forms, poignant characters and haunting décors: all present clues to his introspection. Similar to how doctors analyse their patients’ behaviour and verbal expressions, each of Munch’s dark and disturbing creations are scattered pieces of their creator’s puzzling mind.

His numerous encounters with disease and death fuelled a sense of guilt (as he survived from tuberculosis while his favourite sister, Sophie, and his mother both succumbed to it), as well as a personal fear that illness would inevitably be the painful end of him. Edvard’s austere and extremely pious father further instilled this terror by justifying his wife and daughter’s demise as acts of divine punishment. The Sick Child, a heartbreaking portrayal of his beloved sister before she passed away, perfectly illustrates Munch’s growing obsession with death, after accumulating further losses with his brother surrendering to pneumonia, grandfather dying from spinal tuberculosis and father leaving him behind following a stroke.

This scene, overflowing with unbearable grief, was first painted in 1885 and this traumatic event was painstakingly revisited 6 times during the span of 4 decades. His fixation clearly demonstrated the pervasive psychological impact the theft of his loved ones by illness left him with, while his mental fragility and looming depression emanated from the gloomy and poignant atmosphere. “Illness, madness and death were the black angels that watched over my cradle and have since followed me through life.” Suicidal thoughts soon plagued his mind and found a permanent residence. “I live with the dead—my mother, my sister, my grandfather, my father… Kill yourself and then it’s over. Why live?”

For some decades, Munch’s art, deemed too controversial and immoral by the Norwegian public, remained minimally appreciated, to which the artist took offence. This persecution led to his focus shifting away from the fatality of human existence and towards his developing anxiety, which can best be felt in his most famous piece of art: The Scream. Munch related his inspiration for the painting in what, oddly enough, could be the account of hallucinations experienced during a panic attack, after visiting the schizophrenic Laura Catherine at her mental hospital:

“I was walking along the road with two of my friends. Then the sun set. The sky suddenly turned into blood […] I stood still, leaned against the railing, dead tired. Above the blue-black fjord and city hung clouds of dripping, rippling blood. My friends went on and again I stood, frightened with an open wound in my breast. A great scream pierced through nature.”

Although based on his own experience, the agonising and utterly horrifying protagonist bears no physical resemblance to Munch, or any human being. The genderless creature has been dehumanised, gifted with the fluidity necessary to become a universal symbol of modern angst and existentialism. This piece’s intensity was so overwhelming even Munch declared it “[could] only have been painted by a madman.”

“The second half of my life has been a battle just to keep myself upright.”

In the fall of 1908, auditory hallucinations, as a consequence of psychosis combined with his bipolar disorder, and paralysis accompanied by a manic behaviour culminating in his shooting two joints off his left ring finger during a lover’s quarrel, caused Munch to reluctantly check himself into a private sanatorium in Copenhagen. There, his excessive drinking significantly reduced, and a regained sense of mental stability could be felt in his subsequent paintings, with heartfelt optimism emerging from the brighter and lighter choices of colours. This illustrates how one’s psychological state alters how the world appears and is interpreted; similarly, every patient’s experience with a disease or treatment will be different.

Ultimately, it is crucial to remember that mental illness does not define a person or their achievements- after all, Munch’s artistic talent persisted even in the better years of his life. The narrative of the ‘tortured artist’ comes from a place of idealisation rather than empathy – a look into Munch’s life is a powerful and touching reflection on the damaging effects of mental illness and its unique manifestation depending on the individual, and an appreciation of his contribution to history is a lesson in empathy and understanding. Upon his death in 1944, 1,008 paintings, 4,443 drawings and 15,391 prints were discovered in his estate; his “children” as he liked to call them, constituted the visual diary of his life and witnessed his passing, just as he did with his own family members. “The notes I have made are not a diary […] they are partly extracts from my spiritual life […] My pictures are my diaries.”